BBC News, Thailand 30 March 2016

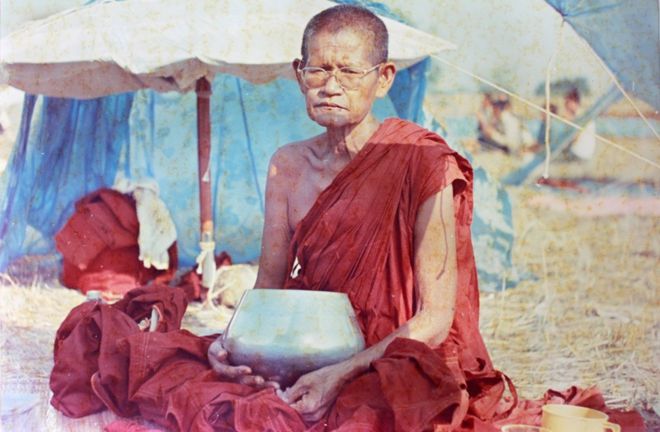

Fifty years ago, Luang Poh Yaai lived as a Buddhist monk - a first for a woman in Thailand where religious authorities bar females from the monkhood. Today some get round the ban by getting ordained abroad and returning to live in monasteries for women.

Fifty years ago, Luang Poh Yaai lived as a Buddhist monk - a first for a woman in Thailand where religious authorities bar females from the monkhood. Today some get round the ban by getting ordained abroad and returning to live in monasteries for women.

The temple of Wat Thamkrabok sits at the foot of a sweeping, craggy outcrop in the countryside north of Bangkok. Its courtyard is shaded by ancient trees.

Once a day, its temporary residents kneel alongside a grate that covers a deep drain, and breathe deeply. Next to each of them is a metal bucket full of drinking water. In turn, they are offered a small glass of dark liquid, poured by a monk from an ancient bottle. They drink.

Within seconds the still air is assaulted by the sound of retching. As the young men vomit into the drain, the monks offer encouragement, tell them to keep drinking water, and place reassuring hands on bare shoulders.

Ying Panyapon

Ying Panyapon

Those undergoing this punishing regime are all drug and alcohol addicts. And it was Luang Poh Yaai who introduced the detox programme to treat opium addiction in 1959. She was an excellent herbalist, and the preparation drunk by the addicts is still made to her recipe.

Beside the temple, away from the courtyard where the addicts are treated, is a workshop - it is the domain of Luang Pi Ai, one of the monks. An old table heaves under the weight of dozens of statues-in-the-making - all representations of Luang Poh Yaai. And there is a life-size, fibreglass figure of her.

Ying Panyapon

Ying Panyapon

"I made this 30 years ago," explains Luang Pi Ai. "It was one of my first and my best because I made it from my soul."

He was ordained at the temple when he was 19, and has a particular reason to feel grateful to Luang Poh Yaai.

"My father was the very first addict to be successfully treated here," he says. "He was an opium addict - back then there was only opium. After he followed the programme here he never touched drugs again."

Ying Panyapon

Ying Panyapon

The details about Luang Poh Yaai's early life are sketchy. According to an account by Ian G Baird, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, as a child she claimed to remember her past lives and communicated with spirits. Later, she married and had two children, but abandoned by her husband, she lived in a Bangkok slum and became an alcoholic.

At the age of 40, or thereabouts, Luang Poh Yaai again remembered her past lives, stopped drinking and became a white-robed Buddhist nun, or mae chee.

In 1957 she founded the temple with her two nephews. By then she was wearing monks' robes.

"One day she understood the truth, and she changed her clothes right away - there was no formal ordination," says the current abbot of the temple, Phra Ajahn Boonsong, who studied under Luang Poh Yaai for three years until she died in 1970.

"If you were an outsider, you wouldn't have guessed she was a woman," he says, though all her followers knew, and no-one expressed concern or disapproval."

Away from her community, however, it could be different.

"Once, she was arrested in another province, and charged with imitating a monk, which is illegal in Thailand," says Phra Ajahn Boonsong.

"She explained to the authorities she had become a monk to stop herself sinning, and not so she could take advantage of anyone else. So eventually they let her go."

Although Luang Poh Yaai's story is still not well-known in Thailand, for some people she's important.

"It seems she had a connection with the divine spirit, and the herbal medicine that she used was told to her by the divine spirit," says the Venerable Dhammananda, a monk since 2001.

Ying Panyapon

Ying Panyapon

Dhammananda is a former academic, TV presenter - and a woman. She travelled to Sri Lanka - where female monks are allowed - to be ordained. She returned home the first Thai woman to be fully ordained in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, and is now abbess at the Songdhammakalyani monastery in Nhakon Pathom, west of Bangkok.

"Back then, I didn't think it was anything great… I was just doing my duty, keeping alive the heritage that the Buddha gave us. But to look back - unless there was that one woman who walked ahead, the movement would not have started."

In Thailand, reactions to Dhammananda were often negative.

"In the beginning… 'Oh! You dare wear the robe!' And I said, 'Well I'm a monk, I'm a female monk, what else do you want me to wear?' It still happens now, but only when I go to a public toilet - they always try to throw me out and send me to the male toilet because they associate the robes with men. But we make a joke of it, and they accept me."

Now there are about 100 women monks in Thailand - all of them ordained abroad. Fifteen women live at the Songdhammakalyani monastery, where life is punctuated by meditation and stillness. The monks work too - maintaining the temple grounds, delivering workshops in prisons, and welcoming members of the public who attend services or come seeking help.

Ying Panyapon

Ying Panyapon

And Dhammananda is about to branch out and establish a new community further south in Thailand.

Compared to some 300,000 men living in monasteries in Thailand, women like Dhammananda are part of a tiny minority. But they may be gaining a better reputation than some of their male counterparts. Repeated allegations in the newspapers about sexual offences, fraud and wildlife trafficking, have led to disillusionment in her community, she says, something the women notice when they go out collecting alms - food, drinks and offerings of flowers.

Ying Panyapon

Ying Panyapon

"Some households have already stopped giving alms to the male monks - they lost respect. And then when they see these female monks coming out, then they start giving alms again."

She also sees growing signs of encouragement for female monks from Thailand's male counterparts.

"Some of them do support us," she says. "More and more on our temple's Facebook page, monks visit to learn about what we do. And when we arranged our latest international ordination in Sri Lanka, many monks said, 'Satu' which means 'Well done' - or they clicked 'Like'."

Phra Ajahn Boonsong, the abbot of Wat Thamkrabok, will not be drawn on whether Thailand should allow the ordination of women. He says only this: "In the Buddhist world there is only one truth, and there is no gender."

Paul has come from Australia in the hope of being cured of his addiction to crystal meth. He is on day four of the detox programme, and is surprised to learn the founder of the temple, and the initiator of his treatment, was a woman - it is not written anywhere in English on the temple's website.

But he knows what he would say to Luang Poh Yaai if she were here.

"Thank you very much for giving us an opportunity to begin a new life. And to anyone who wants to stop their bad habit, welcome to Wat Thamkrabok."

No comments:

Post a Comment