Posted on 21 January 2017 by Buddhism Now

It is beneficial to recite the mantra om mani padme hum, but while you are doing it, you should be thinking of its meaning, for the meaning of the six syllables is great and vast. The first, om, is composed of three letters, a, u, and m. These symbolise the practitioner’s impure body, speech, and mind; they also symbolise the pure exalted body, speech, and mind of a Buddha.

It is beneficial to recite the mantra om mani padme hum, but while you are doing it, you should be thinking of its meaning, for the meaning of the six syllables is great and vast. The first, om, is composed of three letters, a, u, and m. These symbolise the practitioner’s impure body, speech, and mind; they also symbolise the pure exalted body, speech, and mind of a Buddha.

Can impure body, speech, and mind be transformed into the pure, or are they entirely separate? All Buddhas are cases of beings who were like ourselves and then in dependence on the path became enlightened; Buddhism does not assert that there is anyone who from the beginning is free from faults and possesses all good qualities. The development of pure body, speech, and mind comes from gradually leaving impure states and their being transformed into the pure.

How is this done? The path is indicated by the next four syllables. Mani, meaning jewel, symbolises the factors of method—the altruistic intention to become enlightened, compassion, and love. Just as a jewel is capable of removing poverty, so the altruistic mind of enlightenment is capable of removing the poverty, or difficulties of cyclic existence and of solitary peace. Similarly, just as a jewel fulfils the wishes of sentient beings, so the altruistic intention to become enlightened fulfils the wishes of sentient beings.

The two syllables, padme, meaning lotus, symbolise wisdom. Just as a lotus grows forth from mud but is not sullied by the faults of mud, so wisdom is capable of putting you in a situation of non-contradiction, whereas there would be contradiction if you did not have wisdom. There is wisdom realising impermanence, wisdom realising that persons are empty of being self-sufficient or substantially existent, wisdom realising the emptiness of duality—that is to say, the lack of difference of entity between subject and object—and wisdom realising the emptiness of inherent existence. Though there are many different types of wisdom, the main one of all these is the wisdom realising emptiness.

Purity must be achieved by an indivisible unity of method and wisdom, symbolised by the final syllable hum, which indicates indivisibility. According to the sutra system, this indivisibility of method and wisdom refers to wisdom affected by method and method affected by wisdom. In the mantra, or tantric vehicle, it refers to one consciousness in which there is the full form of both wisdom and method as one undifferentiable entity. In terms of the seed syllables of the five Conqueror Buddhas, hum is the seed syllable of Akshobhya—the immovable, the unfluctuating, that which cannot be disturbed by anything.

Thus the six syllables, om mani padme hum, means that in dependence on the practice of a path that is an indivisible union of method and wisdom, you can transform your impure body, speech, and mind into the pure exalted body, speech, and mind of a Buddha. It is said that you should not seek for Buddhahood outside of yourself; the substances for the achievement of Buddhahood are within. As Maitreya says in his Sublime Continuum of the Great Vehicle (uttaratantra, rgyud bla ma), all beings naturally have the Buddha-nature in their own continuum. We have within us the seed of purity, the matrix-of-One-Gone-Thus, that is to be transformed and fully developed into Buddhahood.

[Excerpt from Kindness, Clarity, and Insight, The Dalai Lama, trans. Jeffrey Hopkins, Snow Lion, revised and updated special celebration edition 2006 (see further details on page 35). Courtesy of Snow Lion Publications.

From the November 2001 Buddhism Now.

Kindness, Clarity, and Insight from the Book Depository with free world shipping.

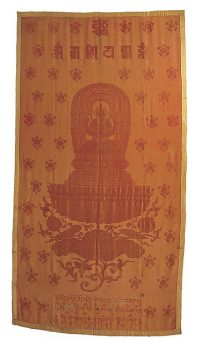

Shadakshari Lokeshvara is the bodhisattva of compassion (Avalokiteshvara) in his role as the lord of the six realms of existence (hell beings, hungry ghosts, animals, humans, demigods, and gods). He personifies the well-known Sanskrit invocation om mani padme hum, or “hail to the jewel in the lotus,” which is found at the top of the hanging beneath the seed syllable hrih, thought to contain the essence of the bodhisattva. The Tibetan-language invocation to the goddess Mahashri at the bottom is often found in the art of the Yongle period.

Shadakshari Lokeshvara is the bodhisattva of compassion (Avalokiteshvara) in his role as the lord of the six realms of existence (hell beings, hungry ghosts, animals, humans, demigods, and gods). He personifies the well-known Sanskrit invocation om mani padme hum, or “hail to the jewel in the lotus,” which is found at the top of the hanging beneath the seed syllable hrih, thought to contain the essence of the bodhisattva. The Tibetan-language invocation to the goddess Mahashri at the bottom is often found in the art of the Yongle period.

Impeccably woven in a single color, the hanging’s damask weave structure and silk fiber impart a certain luminosity to the bodhisattva, lotus, and inscriptions, but they also make the picture somewhat elusive. The image seems to shimmer and change depending upon the light and the viewer’s position. A photograph of the center of the hanging is shown here for your reference. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

No comments:

Post a Comment