Buddhistdoor Global 2016 0 09-09

Between the full moon of September 2016 and the full moon of September 2017 there will be worldwide commemorations of the 2600th anniversary of the bhikkhuni sangha[1]. One hundred years ago, the bhikkhuni sangha had disappeared in all Buddhist traditions except those of East Asia, but recent years have witnessed the nurturing and revival of this integral aspect of the historical Buddha’s Fourfold Sangha. An occasion of such import requires reflection and calls on us to take stock of where we are now—and of how much has changed, for bhikkhunis and the Fourfold Community of the Buddha, in the past century!

Mahapajapatī Gotami Theri and bhikkhuni arahants from a Gandha Kuti in Pagan, Myanmar. Image courtesy of Lilian Handlin's May 26 University of Hamburg/Numata Center for Buddhist Studies lecture “Depictions of Women in Myanmar Gandhakuti(s) During the Second Millenium.” From Ayya Tathaaloka Bhikkhuni Facebook

Mahapajapatī Gotami Theri and bhikkhuni arahants from a Gandha Kuti in Pagan, Myanmar. Image courtesy of Lilian Handlin's May 26 University of Hamburg/Numata Center for Buddhist Studies lecture “Depictions of Women in Myanmar Gandhakuti(s) During the Second Millenium.” From Ayya Tathaaloka Bhikkhuni FacebookAs I reflect on my own past, I remember my young teenage years—a time

in which many young men enter monastic life as novices in the Theravada traditions of South and Southeast Asia. But I was a young teen in the rural northeast of Washington State during the 1980s. In my family’s home library

I encountered a volume published by the Pali Text Society. In it, I read about learned and lauded female monastics, leaders, and teachers who lived during the time of the Buddha in his monastic community. As I already had much appreciation for other things I had heard about the Buddha, this new information came as no surprise as it seemed highly fitting of my admiring

and appreciative understanding of the Awakened One.

A family friend, recently returned from Thailand, visited us around that time.

He had entered a Thai Buddhist monastery and temporarily ordained as a bhikkhu for the three months of the Vassa (rains retreat). He shared a rather different perspective—how he, or any man, could ordain at a monastery for

a period of time (or for their entire life) and receive higher training in sila

(ethics and moral virtue),samadhi (meditation), and panna (wisdom), with complete social and community support. But when I expressed interest in this opportunity, I was cut short and told that it was a possibility traditionally not available to women, who could hope and try their best to be reborn as men

if they wished to take that path. I was deeply shocked and jarred—could this

be true?

He had entered a Thai Buddhist monastery and temporarily ordained as a bhikkhu for the three months of the Vassa (rains retreat). He shared a rather different perspective—how he, or any man, could ordain at a monastery for

a period of time (or for their entire life) and receive higher training in sila

(ethics and moral virtue),samadhi (meditation), and panna (wisdom), with complete social and community support. But when I expressed interest in this opportunity, I was cut short and told that it was a possibility traditionally not available to women, who could hope and try their best to be reborn as men

if they wished to take that path. I was deeply shocked and jarred—could this

be true?

However, there were supportive movements afoot. The Sakyadhita

International Association of Buddhist Women was formed in India in the

mid-1980s. At the first gathering, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, shedding

tears of compassion, spoke encouragingly of the revival of the full bhikkhuni ordination in his own Nalanda tradition, as well as other traditions in which it had been lost, including the Theravada. A number of leading elder Theravada bhikkhus in India concurred. Research was called for into the still-extant bhikkhuni traditions of East Asia.

International Association of Buddhist Women was formed in India in the

mid-1980s. At the first gathering, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, shedding

tears of compassion, spoke encouragingly of the revival of the full bhikkhuni ordination in his own Nalanda tradition, as well as other traditions in which it had been lost, including the Theravada. A number of leading elder Theravada bhikkhus in India concurred. Research was called for into the still-extant bhikkhuni traditions of East Asia.

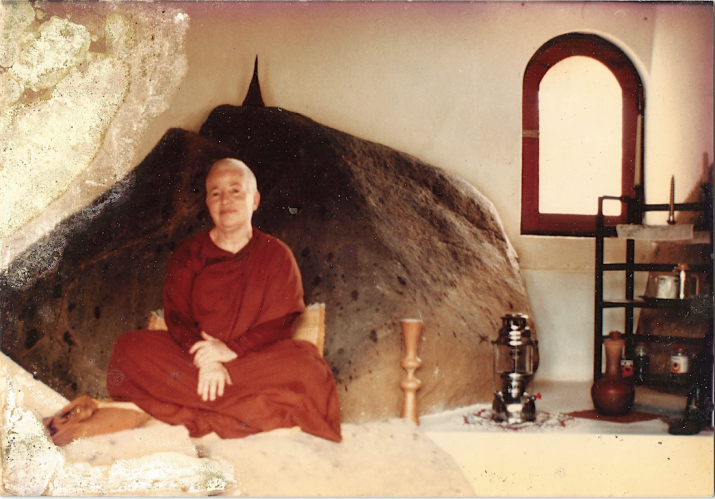

Ayya Khema at Parappduduwa Nun’s Island in Sri Lanka. From youtube.com

Ayya Khema at Parappduduwa Nun’s Island in Sri Lanka. From youtube.com

This was soon followed in 1988 by the bhikkhuni ordination of Ayya Khema

and her Theravada peers from Germany, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the US—in

which my own preceptor-to-be, Ven. Dr. Havanpola Ratanasara, played such

an important role. This became the first swell in a rising tide of support for

the revival of full bhikkhuni ordination. Eventually, I too went forth into

monastic life, traveling first to Europe, then India, and then East Asia, where

the ancient bhikkhuni lineage still existed, brought in the 3rd century BCE by Sanghamitta Theri, eldest daughter of Emperor Ashoka, from India to Sri

Lanka, and by her bhikkhuni heirs from Sri Lanka to China.

and her Theravada peers from Germany, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the US—in

which my own preceptor-to-be, Ven. Dr. Havanpola Ratanasara, played such

an important role. This became the first swell in a rising tide of support for

the revival of full bhikkhuni ordination. Eventually, I too went forth into

monastic life, traveling first to Europe, then India, and then East Asia, where

the ancient bhikkhuni lineage still existed, brought in the 3rd century BCE by Sanghamitta Theri, eldest daughter of Emperor Ashoka, from India to Sri

Lanka, and by her bhikkhuni heirs from Sri Lanka to China.

In the research department of Unmoon Bhikkhuni Sangha College in central South Korea, I studied Comparative Vinaya and World Bhikkhuni Sangha

History under the auspices of my most venerable and compassionate Korean bhikkhuni mentor and sponsor, Myeong Seong Sunim,[2] herself a master Dharma teacher. Reaching back to and mining the ancient stories of the great female Buddhist masters,[3] and meeting such contemporary living masters, courage, vision, and a sense of possibility began to flow into me—and into others. A growing number of scholars began to join this work, articles and

books were written,[4] and lives changed. Reclaiming history (or “her-story”) has enormous power to support. No wonder the Buddha recommended and advised the practice of Sanghanusati (recollection of the excellent qualities of the sangha and of the leading masters and teachers—including bhikkhunis!).

History under the auspices of my most venerable and compassionate Korean bhikkhuni mentor and sponsor, Myeong Seong Sunim,[2] herself a master Dharma teacher. Reaching back to and mining the ancient stories of the great female Buddhist masters,[3] and meeting such contemporary living masters, courage, vision, and a sense of possibility began to flow into me—and into others. A growing number of scholars began to join this work, articles and

books were written,[4] and lives changed. Reclaiming history (or “her-story”) has enormous power to support. No wonder the Buddha recommended and advised the practice of Sanghanusati (recollection of the excellent qualities of the sangha and of the leading masters and teachers—including bhikkhunis!).

Already a bhikkhuni myself by then,[5] I visited Thai monasteries famed for meditation and walked (Thai: thudong, Pali: carika) through Northeast

Thailand. This was the homeland of the forest traditions of Ajahn Chah,

Ajahn Maha Bua, and Ajahn Mun. There I found that many ordinary people

—and many younger bhikkhus and a surprising number of senior monastic teachers—were highly supportive and encouraging of my being a bhikkhuni,

and of women having the opportunity to ordain with a female teacher. They even brought female students and relatives to me, asking me to ordain them, although I did not yet have the seniority Vinaya recommends to do so.[6]

Such a surprise!

Thailand. This was the homeland of the forest traditions of Ajahn Chah,

Ajahn Maha Bua, and Ajahn Mun. There I found that many ordinary people

—and many younger bhikkhus and a surprising number of senior monastic teachers—were highly supportive and encouraging of my being a bhikkhuni,

and of women having the opportunity to ordain with a female teacher. They even brought female students and relatives to me, asking me to ordain them, although I did not yet have the seniority Vinaya recommends to do so.[6]

Such a surprise!

The author serving as preceptor for Samaneri Pabbajja at Nirotharam bhikkhuTni arama in Thailand, 2010. Image courtesy of Nirodharam Bhikkhuni Arama

The author serving as preceptor for Samaneri Pabbajja at Nirotharam bhikkhuTni arama in Thailand, 2010. Image courtesy of Nirodharam Bhikkhuni Arama

Compounding my surprise, fragments of a bhikkhuni history in the area

began to appear.[7] The tradition was not nearly so bereft as it had been rumored to be 20 years earlier, and it began to appear less bereft to a

growing number of others as well. The close of the 20th century saw the

revival of the Theravada bhikkhuni sangha in both Sri Lanka and India. By

the beginning of the 21st century, the number of bhiksuṇi teachers in Tibetan Buddhism and bhikkhuni teachers in Theravada Buddhism was on the rise,

with the emergence of wise and eminent fully ordained female monastics.

The first decade saw the appearance of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis, and the Dalai Lama’s call for the first International Congress on Buddhist Women’s

Role in the Sangha. We also learned much about the legality of bhikkhuni ordination and the Buddha’s intention for a Fourfold Community from

eminent scholars such as Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi [8] and Ven. Bhikkhu Analayo.[9] The number of bhikkhunis in Sri Lanka had risen to more than 1,000,

and the numbers in Thailand and the US were rising in tandem, with

Theravada bhikkhuni teachers of growing experience and seniority beginning

to appear as lamps and luminaries.

began to appear.[7] The tradition was not nearly so bereft as it had been rumored to be 20 years earlier, and it began to appear less bereft to a

growing number of others as well. The close of the 20th century saw the

revival of the Theravada bhikkhuni sangha in both Sri Lanka and India. By

the beginning of the 21st century, the number of bhiksuṇi teachers in Tibetan Buddhism and bhikkhuni teachers in Theravada Buddhism was on the rise,

with the emergence of wise and eminent fully ordained female monastics.

The first decade saw the appearance of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis, and the Dalai Lama’s call for the first International Congress on Buddhist Women’s

Role in the Sangha. We also learned much about the legality of bhikkhuni ordination and the Buddha’s intention for a Fourfold Community from

eminent scholars such as Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi [8] and Ven. Bhikkhu Analayo.[9] The number of bhikkhunis in Sri Lanka had risen to more than 1,000,

and the numbers in Thailand and the US were rising in tandem, with

Theravada bhikkhuni teachers of growing experience and seniority beginning

to appear as lamps and luminaries.

The number of dedicated communities for Theravada bhikkhunis in the West is also on the rise, whether bhikkhuni monasteries associated with bhikkhu monasteries (such as Dhammasara Nuns Monastery and Bodhinyana Monastery in Western Australia), independent bhikkhuni viharas andaramas (such as Dhammadharini, Aloka Vihara Forest Monastery, and Mahapajapati Monastery in the US, Sati Saraṇiya Hermitage in Canada, Anenja Vihara in Germany, and Santi Forest Monastery in Australia), and the first dual-sangha monastery in the West, Newbury Buddhist Monastery in Australia. In the past two years alone, we have witnessed the revival of the ancient bhikkhuni sangha of Bangladesh, and the first public Theravada bhikkhuni ordinations in Thailand,[10] Germany, and Indonesia,[11] and the first bhikkhuni aramas open in places as far afield as the Czech Republic.[12]

Ven. Bhikkhuni Visuddhi from the Czech Republic with an elder bhikkhuni teacher and sangha members in Sri Lanka. Image courtesy of Karuna Sevena

Ven. Bhikkhuni Visuddhi from the Czech Republic with an elder bhikkhuni teacher and sangha members in Sri Lanka. Image courtesy of Karuna Sevena

The role of women as teachers and leaders in secular society is on the rise in both the East and West. Old dogmas and prejudices are being challenged. Female monastics are gaining wider recognition and prominence as teachers

and leaders in Buddhism, as in ancient times under the Buddha’s guidance.

and leaders in Buddhism, as in ancient times under the Buddha’s guidance.

Theravada bhikkhuni-theri [13] teachers from Germany, Indonesia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, the US,[14] and Vietnam have been appointed and begun to serve as bhikkhuni preceptors. Those few bhikkhunis still alive who were ordained in 1988 are mahatheris (great elders), and those ordained in the groundbreaking ordinations of 1996–8 are becoming mahatheris during this 2,600-year commemoration. With this great hurdle surpassed, the Theravada tradition will no longer be lacking in mahatheris—great female monastic elders, teachers, and preceptors.

Preceptor Ven. Bhikkhuni Dhammananda of Thailand with Thai bhikkhuni sangha members. From kyotoreview.org

Preceptor Ven. Bhikkhuni Dhammananda of Thailand with Thai bhikkhuni sangha members. From kyotoreview.org

Most of the challenges in Asia have been at the institutional level, while one

of the main challenges for bhikkhuni communities in the US, such as Dhammadharini, is requisite support.[15] In Asian Buddhism, elders and traditions are highly valued, and the ways of the most recent teachers often appear nearer to us—our direct example—than the life of the Buddha so long ago. Yet the current of inspiration flowing directly from our vision and recollection of the historical Buddha, from the earliest known Buddhist teachings, and from the early sangha is growing stronger due to greater

public access to the teachings. The early Buddhist teachings are being

liberated internationally in a way perhaps unprecedented since the Blessed One’s own lifetime.

of the main challenges for bhikkhuni communities in the US, such as Dhammadharini, is requisite support.[15] In Asian Buddhism, elders and traditions are highly valued, and the ways of the most recent teachers often appear nearer to us—our direct example—than the life of the Buddha so long ago. Yet the current of inspiration flowing directly from our vision and recollection of the historical Buddha, from the earliest known Buddhist teachings, and from the early sangha is growing stronger due to greater

public access to the teachings. The early Buddhist teachings are being

liberated internationally in a way perhaps unprecedented since the Blessed One’s own lifetime.

Ven. Kahanda Amarabuddhi Mahathero, chief prelate of the Sri Lankan Sangha in California, offering words of blessing and Dhamma encouragement at the inaugural blessings of the new Dhammadharini Monastery. From of Philip Rathle Facebook

Ven. Kahanda Amarabuddhi Mahathero, chief prelate of the Sri Lankan Sangha in California, offering words of blessing and Dhamma encouragement at the inaugural blessings of the new Dhammadharini Monastery. From of Philip Rathle Facebook

This transformation could not come at a time of greater need—our world

is suffering from a majorwisdom deficit. There is a rising understanding

that true, honest, and trustworthy morality and ethics are gravely needed,

and we rightly sense that our very lives and future depend on these qualities. Calm, clarity, balance, and insight are necessary to face the personal, interpersonal, and global challenges of our times. The original Fourfold

Sangha was an optimal structure for sharing Dhamma medicine with all

levels of society, and historically we know it was highly successful.

is suffering from a majorwisdom deficit. There is a rising understanding

that true, honest, and trustworthy morality and ethics are gravely needed,

and we rightly sense that our very lives and future depend on these qualities. Calm, clarity, balance, and insight are necessary to face the personal, interpersonal, and global challenges of our times. The original Fourfold

Sangha was an optimal structure for sharing Dhamma medicine with all

levels of society, and historically we know it was highly successful.

The Fourfold Sangha’s main function is to offer the very best opportunity

and support to each and every person who would take this Dhamma medicine, heal themselves, and share that medicine with our world. This medicine is

much needed. But in some of the greatest Buddhist traditions, otherwise so strong, the sangha itself is partially crippled and unbalanced, unable to fulfill

its full noble potential with any one of the four pillars not fully enabled.

Clearly, our way as Buddhists should be to do everything we can to uplift ourselves and one another from the mire of ignorance, delusion, and intoxication in which we are embroiled, and to empower all those who are

able to do so.

and support to each and every person who would take this Dhamma medicine, heal themselves, and share that medicine with our world. This medicine is

much needed. But in some of the greatest Buddhist traditions, otherwise so strong, the sangha itself is partially crippled and unbalanced, unable to fulfill

its full noble potential with any one of the four pillars not fully enabled.

Clearly, our way as Buddhists should be to do everything we can to uplift ourselves and one another from the mire of ignorance, delusion, and intoxication in which we are embroiled, and to empower all those who are

able to do so.

The Buddha was unequivocal about women having this full capability, both

for awakening and serving in leadership capacities. He was unequivocal

about his intention, stating very shortly after the time of his great

awakening—even before he began teaching—that a Fourfold Sangha

including bhikkhunis was an essential part of his plan for his Sasana (dispensation).[16] In fact, he asked all Buddhists to direct their daughters

to look to his two leading bhikkhuni disciples, Khema of Great Wisdom and Uppalavaṇṇa of Great Spiritual Power, as role models and exemplars, and for

all female monastics to look to them.[17] They were bhikkhuni leaders,

rightly termed the Buddha’s full-fledged heirs.

for awakening and serving in leadership capacities. He was unequivocal

about his intention, stating very shortly after the time of his great

awakening—even before he began teaching—that a Fourfold Sangha

including bhikkhunis was an essential part of his plan for his Sasana (dispensation).[16] In fact, he asked all Buddhists to direct their daughters

to look to his two leading bhikkhuni disciples, Khema of Great Wisdom and Uppalavaṇṇa of Great Spiritual Power, as role models and exemplars, and for

all female monastics to look to them.[17] They were bhikkhuni leaders,

rightly termed the Buddha’s full-fledged heirs.

Tile fresco of the leading disciple of the Buddha Uppalavaṇṇa Theri from Noppapolbhumisiri Chedi (the Queen’s Chedi), Doi Inthanon, Thailand. Image courtesy of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis

Tile fresco of the leading disciple of the Buddha Uppalavaṇṇa Theri from Noppapolbhumisiri Chedi (the Queen’s Chedi), Doi Inthanon, Thailand. Image courtesy of the Alliance for Bhikkhunis

Let us revive this spirit, the spirit of the Buddha himself and the spirit of

the great masters, to do all we can to unobstruct and unhinder ourselves

and each other, using the full means and heritage gifted to us by the

Blessed One. Let us close the door to none—not for gender, race, caste, class,

or background. The work is so great—we need all of the good people who are willing and able to step forward for this most noble task at hand.

the great masters, to do all we can to unobstruct and unhinder ourselves

and each other, using the full means and heritage gifted to us by the

Blessed One. Let us close the door to none—not for gender, race, caste, class,

or background. The work is so great—we need all of the good people who are willing and able to step forward for this most noble task at hand.

As the moon waxes full on Binara Poya Day—the September full moon remembered by the Sri Lankan Theravada sangha as the lunar commemorative date of the founding of the bhikkhuni sangha and of the fulfillment of the Buddha’s intention to have a complete Fourfold Community 2,600 years ago—

let us take stock, turn our hearts to the bright core vision of the Buddha—awakening—and do everything we can to fully enable the whole sangha and share the benefits of the Path with others, as the Blessed One asked of his Sangha: “For the happiness of the many, for the welfare of the many.”[18]

let us take stock, turn our hearts to the bright core vision of the Buddha—awakening—and do everything we can to fully enable the whole sangha and share the benefits of the Path with others, as the Blessed One asked of his Sangha: “For the happiness of the many, for the welfare of the many.”[18]

Ven. Bhikkhuni (Ayya) Tathaloka Theri, born in the US, is a 30-year monastic with a background in Zen and Theravada Buddhism. She is best known as the co-founder of Dhammadharini (“Women Upholding the Dhamma”), for her work with Comparative Vinaya scholarship and the History (or Her-story) of the Bhikkhuni Sangha, and for being the first contemporary Western woman to be appointed and to serve as a Theravada bhikkhuni preceptor.

[1] The dating of the 2600th anniversary of the bhikkhuni sangha and the establishment of the Fourfold Community of the Buddha between the

September full moons of 2016 and 2017 is in accordance with the Theravada Buddhist calendar dates for the Buddha’s Parinibbana. The foundation of the bhikkhuni sangha five years after the Buddha first began to teach appears in

the canonical Pali texts in the Kuddhaka Nikaya “Theri Apadana” text. The Sri Lanka Theravada Buddhist Sangha remembers and commemorates the

founding of the bhikkhuni sasana on the day of the September full moon,

known as Binara Poya in the Sinhala language.

September full moons of 2016 and 2017 is in accordance with the Theravada Buddhist calendar dates for the Buddha’s Parinibbana. The foundation of the bhikkhuni sangha five years after the Buddha first began to teach appears in

the canonical Pali texts in the Kuddhaka Nikaya “Theri Apadana” text. The Sri Lanka Theravada Buddhist Sangha remembers and commemorates the

founding of the bhikkhuni sasana on the day of the September full moon,

known as Binara Poya in the Sinhala language.

[2] See the fourth from last paragraph to learn more on her life:https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/reflections-from-sakyadhita-conference

[3] See “Precedent from Early Arahants On the Bestowal of Bhikkhuni Ordination,” “Going Forth & Going Out ~ the Parinibbana of Mahapajapati Gotami,” “Amazing Transformations of Arahant Theri Uppalavanna,” “Lasting Inspiration: A Look into the Guiding and Determining Mental and Emotional States of Liberated Arahant Women in Their Path of Practice and its Fulfillment as Expressed in the Sacred Biographies of the Theri Apadana”.

[4] See Alice Collett’s Women in Early Indian Buddhism and Lives of Early Buddhist Nuns, Wendy Garling’s newStars at Dawn, Susan Murcott’s First Buddhist Women and Charles Hallisley’s new translation of the Therigatha, Kathryn Ann Tsai’s “Lives of the Nuns: Biographies of Chinese Buddhist Nuns from the Fourth to Sixth Centuries,” Ven Karma Lekshe Tsomo’s “Sisters in Solitude: Two Traditions of Buddhist Monastic Ethics for Women. A Comparative Analysis of the Chinese Dharmagupta and the Tibetan Mulasarvastivada Bhiksuni Pratimoksa Sutras,” Ven. Wu Yin’s Choosing Simplicity: A Commentary on the Bhikshuni Pratimoksha; Ven Bhikkhu Sujato’s Bhikkhuni Vinaya Studies; “Buddhist Nuns,” JIABS, Vol. 24, No. 2 (2001), “Women’s Contributions to Buddhism: Selected Perspectives,” Sati Journal: the Journal of the Sati Center for Buddhist Studies, Vol. 2 (2014)

[5] In 1997, nearly 10 years after going forth, after two years training as a samaneri, I was fully ordained as a bhikkhuni by the Sri Lanka bhikkhu sangha led by my late most venerable preceptor Ven. Dr. Havanpola Ratanasara Nayaka Mahathero via the Pali text upasampada at the International Buddhist Meditation Center in Southern California, together with bhikkhunis from Sri Lanka and Nepal. Although not a dual ordination, my ordination was sponsored and supported by bhikkhuni masters: my own most venerable bhikkhuni mentor Ven. Dr. Myeong Seong Sunim (from afar); and the late Ven. Dr. Karuna Dharma, the late Ven. Prabhasa Dharma, and Ven. Ayya Chan Nhyu (all in person).

[6] The Vinaya asks that bhikkhus or bhikkhunis have 10 years seniority, together with other qualifications, before granting pabbajja (the “going forth”) ordination. When I returned to Thailand 7–8 years later in 2010 and such requests were again made, I did then serve as preceptor.

[9] Ven. Bhikkhu Analayo’s “Women’s Renunciation in Early Buddhism: The Four Assemblies and the Foundation of the Order of Nuns” is one chapter of Dignity & Discipline, the book which arose out of the Congress. See also Ven. Analayo’s subsequent articles, “The Legality of Bhikkhuni Ordination,” “The Four Assemblies and Theravada Buddhism,” “Theories on the Foundation of the Nuns' Order – A Critical Evaluation,” “The Cullavagga on Bhikkhuni Ordination,” “The Gurudharma on Bhikṣuṇi Ordination in the Mūlasarvastivada Tradition” and “The Going Forth of Mahapajapati Gotami in T 60”. His new book on the subject is The Foundation History of the Nuns’ Order.

[11] See “Blessings for Historic June 21 Bhikkhuni Ordinations in Indonesia and Germany” and “News from the First Theravada Bhikkhuni Ordination in Indonesia in a Thousand Years”

[13] The words thera (m) or theri (f) refer to elders in the monastic tradition of 10 or more years’ seniority. Mahathera (m) or mahatheri (f) refers to “great elders” of 20 or more years’ seniority.

[14] In 2009, the author became the first western woman to be appointed and serve as a Theravada bhikkhuni preceptor (pavattini-upajjhaya) in contemporary times.

[15] The majority of Asian Theravada bhikkhu temples in the West are faithfully supported by their associated Asian expatriate communities. The majority of international or western Theravada bhikkhu monasteries also receive great support from the communities in their Asian homelands, i.e., support from Northeastern Thailand for international monasteries of the Thai forest tradition of Ajahn Chah abroad. Although improving, this is generally not nearly at the same degree for bhikkhuni communities in the West.

[16] Long Discourses of the Buddha “Mahaparinibbana Sutta” DN 16 (PTS: DN ii 72), section 18:https://suttacentral.net/en/dn16

[17] See Connected Discourses of the Buddha SN II.17, 24(4) and Numerical Discourses of the Buddha AN I.98 (XII, 131(2)) as well as AN II.164 (176(6)(2))

[18] Bahujana hitaya, bahujana sukhaya. Vinaya: Mahavagga 1.11(1)

No comments:

Post a Comment